Introduction

The archaeological museum risks being a place of mono sensory double jeopardy. The historic paucity of sensory approaches to archaeology might mean that the collection lacks a scholarly understanding of its multisensory context — a problem addressed by the recent proliferation of sensory approaches to archaeology exemplified in this Special Issue, Sensory Experiences in the Roman North. However, the ocular and information-centrism of traditional museum displays can also mean that visitors predominantly interface with archaeological collections visually and cognitively. There has recently been a ‘comeback’ for multisensory interpretation of collections in the practice of museology, which has challenged the archaeological museum to engage visitors via touch, smell, and sound (Dudley 2010; Levent and Pascual-Leone 2014; Skeates and Day 2019: 1–4; Howes 2022: 163–180). This chapter examines a particular instance in which an attempt has been made at multisensory interpretation as part of an effort to restore an archaeological museum to a locus of embodied experience — i.e. a place where the non-visual senses are deployed in the interpretation of collections to prompt the visitor’s corporal, as opposed to predominantly cognitive, stimulation (Foster 2011; De Caro 2015; Howes 2022). The challenge of restoring the senses, particularly touch, as a means of engaging with archaeological collections is acute. Until the last few decades, museological consensus prohibited physical engagement with objects on the grounds of preservation and social propriety (see e.g. Howes 2022). As part of a reinterpretation project at Chesters Roman Fort, Hadrian’s Wall, English Heritage collaborated with a team of designers from Sheffield Hallam University in an attempt to explore a collection of Roman archaeological stonework in an archetypical, antiquarian museum devoted to the history of excavation and collecting along Hadrian’s Wall (Petrelli et al. 2018). In this museological context, with parameters deeply unfavourable to the sensory explorations of the collection, the interactive installation My Roman Pantheon (MRP from here on) used elements of the Internet-of-Things technology in order to harness the psychophysical components of touch (Paterson 2007), and audio-visual mise-en-scene. MRP immersed visitors in, and empowered them to explore, a religious landscape analogous with that of people living along the erstwhile frontier of Roman Britain, changing visitor behaviour, and restoring a collection of archaeological stonework as loci of embodied experience.

Interpreting an Antiquarian Museum

MRP was installed at Chesters Roman Fort and the Clayton Museum on Hadrian’s Wall in February 2017. Built around AD 120, Hadrian’s Wall was part of the border of the Roman province of Britannia and was a military installation and community of thousands of people for over 300 years (Hodgson 2017: 7–23). Today, the Wall still dominates the landscape, as a distributed, ancient historic monument over 70 miles in length with a complex and deep material record. Its broad scope supports a multitude of heritage experiences (Adkins et al. 2011), with English Heritage running four pay-to-enter heritage sites displaying archaeological remains and museums. Although they share a common overarching history, each has a distinct archaeological profile, landscape setting, and vastly divergent museum displays. Between 2010 and 2018, each was re-presented with a view to enhancing the specific feel and significance of each site and collection; the interpretive offer was updated and improved for existing audiences and, crucially, the style and types of display were broadened with a view to diversifying the visitorship (Roberts 2021).

From 2015 to 2017, Chesters Roman Fort was reinterpreted. The fort was excavated between the 1840s and 1890s by the estate’s owner, lawyer, and antiquarian, John Clayton (McIntosh 2019). Created in 1896, the Clayton Museum contains Roman archaeological finds from these excavations and those conducted by Clayton and others throughout the wider Hadrian’s Wall area.

When English Heritage convened the Chesters Reinterpretation Project, the team determined that both the museum’s collection and its presence and form were uniquely significant due to the founding role of John Clayton in the preservation and popularisation of Hadrian’s Wall (in addition to Chesters’ archaeological importance as a Roman cavalry fort). The dominant narrative at the three other English Heritage sites is, naturally, the frontier’s Roman history. Particularly with visitors often visiting more than one site, the team felt there was space for a museum that focused on the Wall’s later history and rediscovery. Audience evaluations demonstrated that Chesters’ antiquarian story, alongside its role as a cavalry fort, was highly valued by visitors, particularly for the Culture Seekers, who were the primary audience to be engaged by the project. This is the group of visitors that English Heritage audience research describes as visitors with high prior knowledge and a generally high engagement with heritage who tend to prefer information-led exhibits and like written information.1 Narratively, Chesters was the ideal place to present its rediscovery, excavation, and conservation in the nineteenth century by John Clayton and others. It was therefore determined that the new display should retain Chesters’ Edwardian character and preserve the antiquarian feel of the museum, albeit while updating the graphics and making it easier to find and browse through information on an often overwhelming collection.2 Therefore, the object spreads remained mainly typological, reflecting Edwardian approaches to objects and epistemologies, designed to reveal the pathway to an understanding of Hadrian’s Wall and Roman material culture on the frontier.3

The main exhibition planned to continue the predominantly textual, information-centric, approach, in keeping with the preferences of the primary audience. The project team, however, wanted to develop a complementary interactive experience — that became MRP — targeting additional audience segments less interested in antiquarianism, and complement the primary interpretive mode with interaction.4 Visitors known by English Heritage as Experience Seekers, who are not specifically seeking or interested in a heritage experience, and Child Pleasers, whose visit is driven by needs and requirements of their children, are generally inclined to discovery-led interpretation and might not be predisposed towards a knowledge or reading-based exhibition. They might prefer interacting within their group during their visit, for example, sharing their thoughts and feelings about what they experienced or else be keen on imaginative modes of learning, such as role play.5 The additional audience groups might be expected to have a limited pre-existing knowledge of, or interest in, a complex epistemological framing of Roman Britain through the lens of antiquarianism. Therefore, MRP was to engage with the Roman period as the primary interpretive lens with Chesters as a Roman cavalry fort, home to a garrison of soldiers and their families.

The presentation style retained at Chesters was not conducive to presenting this narrative to the targeted audiences. The collection, including pottery, jewellery, and decorative metalwork, is still displayed in ‘an antiquarian or simple fashion’ (Derrick 2017: 72–73) — i.e. nineteenth-century-style cases albeit with updated graphics and object-spreads primarily now devoted to telling the story of intellectual discovery (Figure 1). The most visually arresting component of the museum was the large collection of Roman stonework. This comprises inscribed and decorative stones of various forms, including altars dedicated to a range of different deities, and a range of figurative sculptures from temples, shrines, and other buildings from the community of Hadrian’s Wall. They are arrayed en masse, across four tiered rows, around all four walls of the larger of two museum rooms. They dominate the museum space visually and seemingly prime its atmosphere and visitor behaviour.6 Chesters has a ‘temple-like’ feel where visitors often talk in hushed tones and carefully perambulate (Petrelli and Roberts 2023). The heavy presence of the antiquarian gaze is perhaps a strong factor in this behaviour, engendering reverence for the authority and power of the collector, as opposed to the creator or user of the object.7 This may be why many visitors spend very little time in the museum and are particularly reluctant to engage with the stonework.8 Instead, the team wanted visitors to interact with the stonework as objects of great significance to the lives of their erstwhile owners imbued with religious agency, rather than as dusty trophies of antiquarian excavations past, shorn of their Roman context.

A further significant barrier to this engagement was the high bar of knowledge and skills required to understand the stones in context. Whilst the collection contains an array of Roman statue and epigraphic forms recognisable to archaeologists, from the perspective of a lay visitor, they are monochromatic and lacking aesthetic differentiation. Many of the forms are unusual, much are fragmentary or shaped in a way that reveals little about their function or meaning without prior knowledge or without copious reading of labels or the accompanying guide (Figure 2). Many of the altars feature seemingly esoteric symbols, and even someone with a knowledge of Latin will find the inscriptions difficult to grasp, where legible, due to the preponderance of abbreviations. Statues of deities that might be known by non-specialists are not instantly recognisable: perhaps the finest sculpture in the collection is Juno Regina, yet she is headless and standing on a heifer. Many of the deities are rare, even idiomatic, and pose a challenge even to a specialist — for instance, during the evaluation, a visitor was observed reading the name Veteres (also known as Cocidius) on the base of its altar, then telling the children in the group it was ‘veritas’ and was later surprised to read on the postcard it was not. Behind minimal updated graphics, the project did not adjust their display and indeed added a touch-screen kindle — an updated handlist, doubling-down on the antiquarian approach. While this was perhaps of use to those keen on understanding the classification of the stonework, it might not work for visitors in search of a connection with an object used in religious ritual. As Dudley (2010: 4) notes

‘the museum preoccupation with information and the way it is juxtaposed with objects […] immediately takes the museum visitor one step beyond the material, physical thing they see displayed before them, away from the emotional and other possibilities that may lie in their sensory interaction with it’.

To engage the targeted visitor groups the predominant antiquarian lens of the museum needed to be overcome, the stones needed to be reconnected to their original contexts, and the need for prior knowledge or new information reduced. MRP would eschew an information-centric approach and use instead a multisensory experience, incorporating aspects of choice, and harnessing the personal needs and existing knowledge of the visitor. The technical and practical constraints on the experience were restrictive. Direct handling of the objects would have contravened conservation requirements. The new interpretation could not interrupt the predominant museum narrative of antiquarianism or interfere with the Edwardian atmosphere or aesthetics of the Clayton Museum by making significant changes to its architecture. It had to be achieved with a small budget, limited access to electricity due to the paucity of power and specific locations of power sockets, and an unstaffed museum. These factors eliminated, for example, an application dependent upon phone signal, AR and/or VR approaches reliant upon using hardware, or those reliant on constant supervision or resetting after use (for a full description of the technological requirements of MRP, see Petrelli et al. 2018).

Walkthrough of My Roman Pantheon

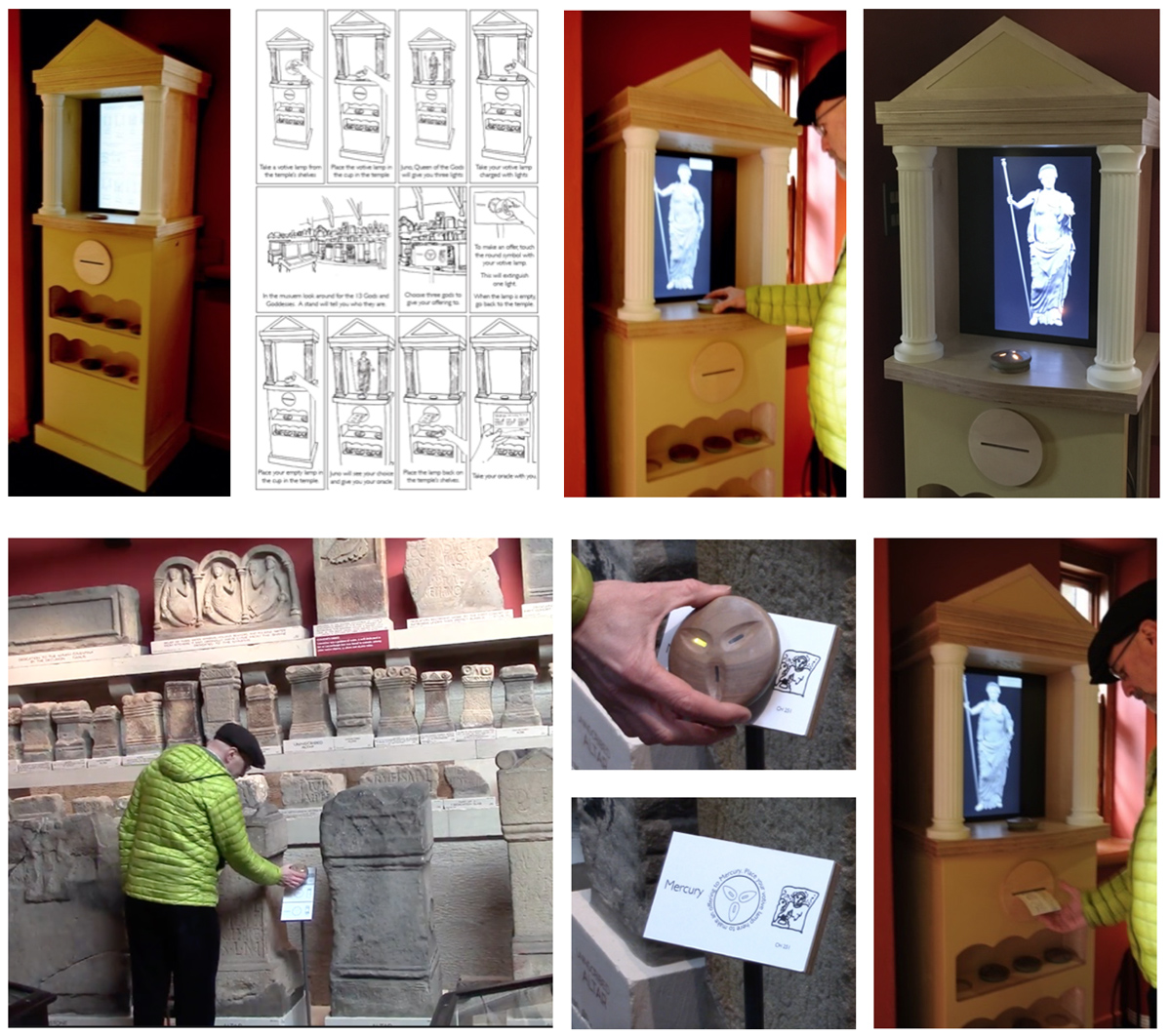

In the vestibule of the Clayton Museum a model of a Roman household altar waits for any curious visitor (Figure 3).

The instructions displayed on the screen encased in the shrine tell them to pick up one of the votive lamps (Figure 4) from the shelves and place it in the bowl at the top of the shrine. The Roman goddess Juno appears within the shrine and welcomes the visitor to Chesters. She informs them that the Roman gods will aid with their life at Chesters, but only if they make appropriate offerings to the gods. At the start the lamp is unlit, but Juno now charges it to display three flickering lights, the three offerings at the visitor’s disposal. She instructs visitors to use their choices wisely and to come back later to receive an ‘oracle’ (Figure 5).

Holding the lamp, visitors pass into the main gallery of the museum and seek out 13 metal stands distributed around the edges of the room amidst the collection of archaeological stonework. Each stand is embedded with Near Field Communication technology (NFC) to communicate with the NFC reader embedded in the lamp. Each stand in the museum displays a symbol matching the votive, the name of a deity who features either figuratively or epigraphically on an item of stonework nearby, and has an outline of the stone to help the visitors to identify the stone among the many.

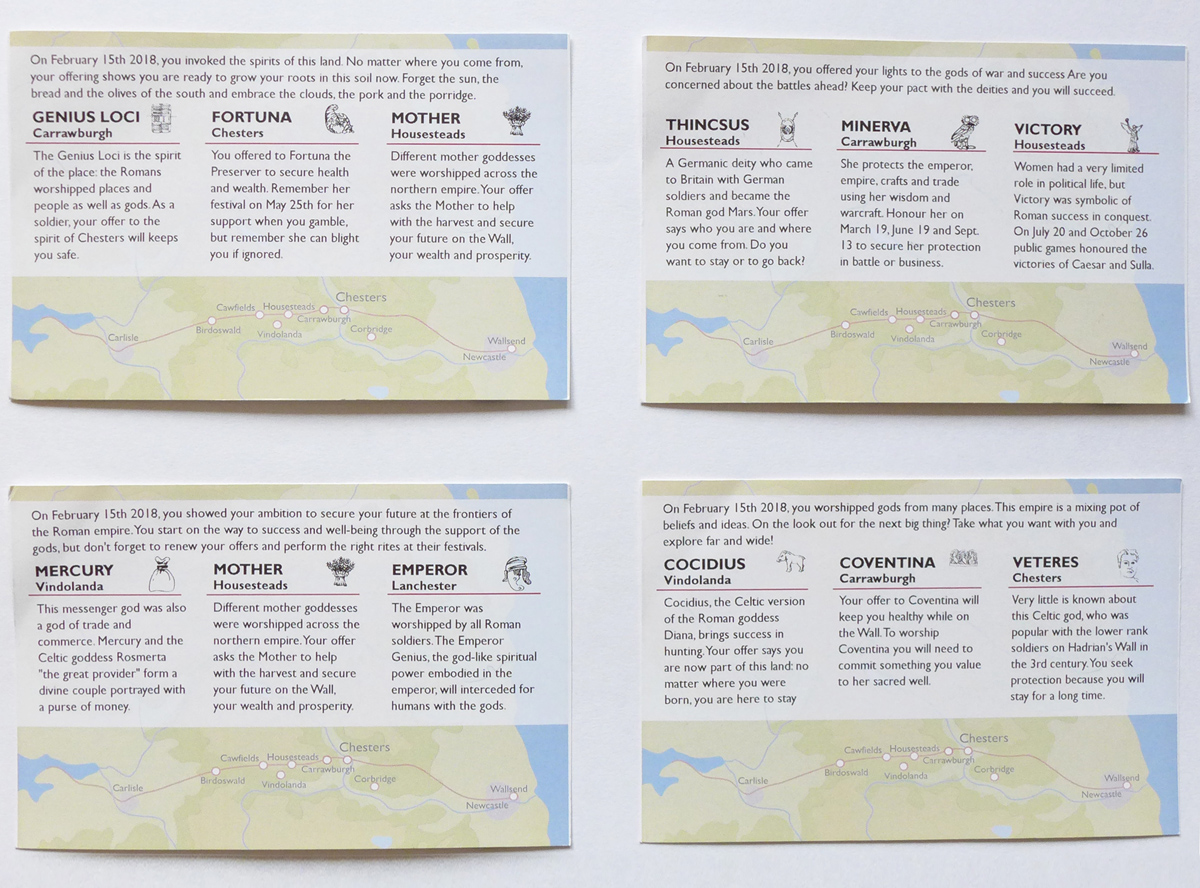

Visitors offer one of their lights by tapping the stands with the votive at which point one light disappears. Once all three lights have been ‘offered’ to different divinities and disappeared the visitor can return to Juno. Upon returning the votive to the cradle of the shrine, Juno congratulates the visitor and the shrine prints a postcard featuring information on up to three chosen deities — My Roman Pantheon — and a personalised ‘oracle’ text that interprets the specific combination of choices.

Principles of an Embodied Experience

The landscape of Roman religion

The interaction design of MRP was premised upon visitors being asked to explore a religious landscape analogous with Roman experience. The first principle was that Romans believed they lived in a world surrounded by gods and goddesses of different types, places, and origins, and that many of these were represented on the stonework in the museum. The gods chosen to be a part of MRP were all worshipped on Hadrian’s Wall and selected specifically to explore the peculiarity of the Roman pantheon. For example, the Romans believed that certain deities had ‘special powers and properties’, and hence, some gods were chosen to show the different goals and needs that people could desire, from health (Asclepius) to wealth (Mercury), victory in life (Fortuna), or on the battlefield (Victoria). The team also chose gods and goddesses that represented the expanding system of beliefs, a consequence of the absorption of the religious practices of conquered lands, in part brought to Hadrian’s Wall by non-Latin populations serving in the garrison. Therefore, the deities chosen for MRP included Mercury and Minerva, traditional gods from Rome, but also Cautes (an attendant of Mithras) from the Middle East, Mars Thinscus from Germany, and Coventina from a sacred well along Hadrian’s Wall. Finally, the Romans believed that the divine inhabited certain people, places, and objects (Hingley 2011: 745–750); this is represented in the museum by Genius Loci (the spirit of the place) and the cult of the emperor (Emperor Genius). The goddess Juno was chosen as the avatar to bookend the experience on the basis that she would be instantly recognisable to the general public as a Roman goddess.9 Such a variety was primarily intended to demonstrate the breadth of deities worshipped by the garrison of Hadrian’s Wall, the cultural diversity of the garrison, and the embedded nature of religion in the Roman world.

Such a wide-ranging pantheon was also intended to stimulate visitor curiosity and offer a wide range of choices that were then interpreted via a written summary of one’s specific pantheon, which was generated according to a weighted algorithm. This was termed an ‘oracle’, which although anachronistic to Roman religion of the frontier, was felt necessary to convey to the layperson the wisdom dispensed by a god or goddess.10 To achieve this, each deity was assigned two of six characteristics which corresponded to the deity’s role in the Roman pantheon:

local – gods originating in the area or closely associated with Hadrian’s Wall.

traditional – those that were cornerstones of the Roman state.

acculturation – gods that Rome had embraced during its expansion.

success – in various forms: life, health, and business.

victory – in military actions.

comradeship – gods showing engagement in soldierly life.

For example, the Emperor, Genius Loci, and Cautes were all tagged with ‘comradeship’ due to their associations with the army and Chesters being a specifically military location, but the Emperor was also tagged with ‘tradition’, Genius Loci as ‘local’, and Cautes as ‘acculturation’ due to Mithraism’s Persian origins. When chosen by the visitors the three deities would form a group of meta-tags, and the balance of the tag-type would determine the wording of the oracle printed as the first thing on the postcard (see examples in Figure 5). A brief caption accompanied each deity to explain their role and, where known, why they might be worshipped. It should be noted that these descriptions were not exhaustive to all aspects of the deity, and represented a necessary simplification of a complex topic to give a sense of why this particular deity would be of immediate significance to the visitor to the Roman fort.11 The postcard also includes the date of the visit making it a unique memento of one’s visit to Chesters.

In addition, the team wanted to convey how the Romans believed that deities could affect your life in profound ways and that their aid could be sought by conducting ritual practice (Hingley 2011: 749). A relationship with chosen gods was secured through prayers and gifts, meaning that an offering of personal value implies a return of favour from the deity. As votives, the Romans used a variety of perishable and non-perishable goods, including food, coinage, and personal use items. The stonework collection were loci of exchange: either they were used — as the altars specifically were — as a site to leave offerings to the Roman god or else were a statement of thanks for the help of the gods. However, MRP was not designed to be a specific analogue of a specific Roman practice or to use the stonework in the way they were intended. Instead, it was a pastiche of Roman and local, non-Latin rituals, tailored to work within the specific interpretive parameters outlined above and for its intended audience. Due to the selection of several different subclasses of stonework, there could not be a ritual that was specifically related to the stones — i.e. an approximation of a sacrifice, the creation of a votive, or the act of leaving a votive in a shrine. The core interactive mechanic, however, was the votive act: to offer something of value — in this case, light — in the hope of favour. The votive device was a stylised Roman lamp with three nooks showing lights (see Figure 4 above). Lamps were often used by the Romans as votives themselves, but the idea of presenting light also evokes other votive acts for example, the Christian practice of lighting candles in church (Garnett 1975). Finally, the requirement to carry and then ‘tap’ the votive, see your lights disappear, and then relinquish the device at the end, was an attempt to capture the act of holding something of value during votive ritual practice, during which your potential success, your life even, might hinge upon investing your ‘votive capital’. Romans, of course, would not have been so limited in their choices, but artificially having a limit of three was to encourage visitors to engage actively in making their choices by engendering the feeling that their ‘votive capital’ was scarce and that there was therefore some consequence involved in giving it up. It was hoped that this would gently push visitors to look around the vast stonework collection, mull over their decisions either by reading the labels or else drawing upon their own knowledge, think about their priorities, and immerse themselves in a task where a ritual act matters; finally, they would receive a reward — the ‘summary’ of their choice — to take away as memento and a return on their investment of their time and choices.

Embodiment via internet-of-things technology

Attempts to deploy sensory engagement with archaeological collections via the means of technology have proliferated; yet, digital interventions in museums can further push the visitor away from the material culture surrounding them, particularly with screen-based approaches that result in visitors looking at screens rather than the exhibition (von Lehn and Heath 2003; Petrelli and O’Brien 2018). Thus, the first design decision for MRP was to eschew screens as the primary means of interaction with the objects (albeit there is a screen used to set up the experience and display instructions). Instead, MRP used technology to divert attention back to the collection of stonework by focusing the visitor’s attention there. This was achieved via the deployment of an Internet of Things technological infrastructure — i.e. digital components embedded into the shrine, the lamp, and the stand. When the votive lamp is swiped over the NFC (Near Field Communicators) on one of the 13 stands, one of the lamp’s LEDs brightens suddenly before being turned off to show the offering has been given. When the lamp is returned to the bowl in the shrine, the lamp communicates to the PC hosted within the shrine the three codes of the offerings to generate the postcard; the PC prints the personalised card and plays the closing animation with Juno handing out the oracle completing the task and concluding the interaction. Concealed and embedded technology in physical objects meant that MRP automatically works intuitively, and in the words of one visitor like ‘magic’ (see below), without interrupting the experience of being present.

Simultaneously, the experience was bookended using mise-en-scene, specifically a 3D setworks of a shrine, two animations, and a prerecorded human voice to give important commands and assurances to the visitor. The shrine was a modern interpretation of a Roman household shrine and conceals a system of inductive charging to recharge the lithium batteries inside the lamps. The welcome animation and the lighting on the lamp are synchronised so that the LEDs are activated when Juno says, ‘… the lights I now put in your votive lamp’, and the lamp she holds lights up, too. The simultaneous switching on of the lights in both the visitor’s and Juno’s lamps is intended to build a tacit agreement between the visitor and Juno — analogous to the relationship between supplicant and deity in Roman religious practice. By taking the lamp with them inside the museum the visitors ‘seal a pact’ to do as instructed. Indeed, not every visitor decided to take this on. The shrine lamps were sometimes charged but not used, a sign some visitors have decided not to take part. Those that do take part enter a relationship with the goddess, walk into the museum with a valuable object to hold, whilst feeling the warmth of the three burning flickering lights. The lamp has been given to you, the visitor, by Juno — who presented herself explicitly as ‘the queen of the gods’ — to exchange your offerings for the gods’ support. You, the visitor, literally have a task in hand.

In addition to sight and sound, MRP actively exploits the sense of touch, both of hand and the body, in order to achieve an embodied experience. Touch is the first sense to develop in the womb; it has its own aesthetics; it is both physical and emotional (Paterson 2007). It is the sense of consciousness and self-awareness: while we see our bodies, we need to kinaesthetically situate our bodies to be aware of ourselves and our place in space. Touch is the only interactive sense (Gibson 1962): we touch, and we are touched in return. Active touch explores the properties of objects, their weight, temperature, texture; passive touch (being touched by the same object) is internalised — we can feel the world through objects (for example, when we use tools) that become an extension of the self (Burton 1993). For the duration of the interaction, holding the lamp becomes the physical representation of the visitor’s will to gift the light to the gods. Hence the design of the experience exploited nuances of touching and being touched in return: the votive lamp has a smooth bottom and a rich wood top with three nooks that invite the finger to play and explore the lamp. The conductive charging makes the bottom of the lamp warm so one has the feeling of really holding a small fire; the flickering light on the dark wood of the light feels precious, warm, and real. The physical act of carrying the lamp brings a body language that expresses affective behaviour. Indeed, objects are perceived as having their own personality and intentions: the lamp wants to be touched and explored, and its interactive behaviour (the lights that flicker and disappear when the offering is done) invites one to act, collaborate, and engage (Sonneveld and Schifferstein 2008). MRP is a pretend game made real by the presence and the use of the lamp.

MRP was intentionally conceived as an embodied experience that mediated the given, complex space of the Clayton Museum and its antiquarian interpretation, the collection, and the visitor. The embodied museum experience is one that can be enhanced or dampened depending on how the space is designed. Exhibition design can harness visitors’ instinctive responses to the space and combine it with non-verbal communication to turn the experience into a dialogue with spaces and objects (Pallasmaa 2014). The visitor first meets Juno, who addresses them directly. They must decide whether to accept the task and take the lamp, or to leave the display, and enter the museum empty handed. MRP therefore offers visitors an avenue to become active with the museum itself becoming a method of discovery (Thomas 2016). However,

‘the museum is only a method, the collection only genuinely a creative technology, if it is sustained and enlivened by enquiry, by exploration of its history and by experimentation with its possibilities in the present’ (Thomas 2016: 141).

The intentional non-digital interactivity of MRP, alongside its tangible components, give a goal for the visit, the motivation to move through the museum, a reason to explore the exhibits, to read the labels and carefully choose between various options, then take away your ‘oracle’ from Juno as a memento of the experience. The design rationale included an intention to allow visitor immersion within the museum, but also to empower them to act — a way to gently force the visitors to immerse themselves in the museum, make informed decisions, and get the ‘summary’ of their choice to take away as a memento.

MRP makes visitors interact with the stones, not with the objects in the case. This interaction should not be underestimated. As visitors are standing in front of the stones they could, in principle, reach out and touch. However, to touch the stones would not provoke any specific engagement besides, potentially, the wonder of touching something that was touched by the Romans. The touching, holding, and engaging with the lamp is part of an elaborate interaction that immerses the visitors into Roman culture and goes well beyond the mere touching of an exhibit. Indeed, the stones are an integral part of the evolving narrative that develops from the interactive experience through the exploration of the museum and the visitor’s personal choices. This is also a very different experience, for example, from the one at a ‘collection handling’ special event where the curator explains the pieces to the audience, or a tactile exploration as offered to visually impaired visitors (Levant and McRainey 2014; Sweetman and Hadfield 2018). In collection handling and tactile explorations of exhibits, visitors explore original pieces guided by a curator or by their own sensorial experience. In both cases, the focus is on the object being touched. With MRP the object touched, the lamp, is not the focus of attention but a means to refocus the visitor’s attention onto the exhibits. Touch is one of the senses engaged in an active visiting experience that requires the visitors to look, move, read, discuss with others to understand, and then decide which gods to offer their limited commodity. It is in the intertwining of the museum collection, narratives (the deities presented), interaction (the requirement to choose three such deities to gift lights), and the physical installation (the shrine, the lamp, the stands, the postcard) that the visit develops as an immersive and personal experience of a special place (Petrelli 2019). MRP mediates between the visitors and Roman culture. It enables visitors to enter the Roman story through the sense of touch and the handling of an object, the lamp, that represents themselves within the past.

Evaluation

MRP has been in use since February 2017.12 Over five years, the authors conducted three separate naturalistic evaluation sessions to assess if and how MRP affected visitors’ behaviour, compared to those visitors that did not engage with MRP. Central to the evaluation were the naturalistic observations of visitors’ behaviour: a researcher mingled with the visitors, observing them at a distance, taking note on how they moved within the museum, how they behaved, and the conversations they had with their visiting partners. On leaving the museum, visitors were invited to fill in a questionnaire and a few follow-up questions were posed by the researchers to those visitors who showed a specific interest and had time to discuss their experience and opinions. Being naturalistic, the dataset captures who was visiting on the days of the evaluation, including working days and weekends, and those who decided to take part. A total of 66 questionnaires (of 40 participants who used MRP and 26 who did not) were collected.13 Challenges faced in collecting responses included the availability of the researchers to visit the site, particularly during COVID lockdowns, and the willingness of participants to undertake the survey. The following evaluation focuses on the observations and the written answers to two open-ended questions (transcribed in full in Appendix A) on using MRP and on the museum experience in general.14

The evaluations sought to assess several aspects of the experience — including usability and demographic information — some of which are beyond the scope of the current paper. This discussion focuses on three desiderata, matching and responding to the aims and challenges outlined above. First, that MRP engaged visitors with the gods and the rituals of Roman religion: i.e. successfully ran an experience counter to the predominant narrative lens of the museum (antiquarian discovery along Hadrian’s Wall). This was demonstrated by reflections on engaging with a world of different gods: ‘I thought that using the Juno device made us talk more while walking around so we had more discussion about the Gods, goddesses and Nymphs’ (P11).15 One visitor even went as far as to say ‘This was one of the most educational places with respect to Roman Religion in Britain that I visited’ (P51). Several visitors actually asked why there had not been more information about the gods, and one said they were using Google while in the museum to find out more about the gods before selecting the three they wanted (P52). This seems to demonstrate an interest in the learning outcomes focused on Roman religion. It suggests that the embodied experience was far from exclusive of other potential means of exploration, and pointed the visitor back towards informative, ocular experience. One young visitor said: ‘It was fun choosing different gods’ and ‘It was interesting to find out about Roman living. More information would be good’ (P16). Similarly, another noted, ‘Brilliant! If we had come to this museum without the digital exhibition my six- and eight-year-olds would have got bored quickly. This exhibition has helped them (and me!) understand the sculptures and Roman religion’ (P55). Responses to MRP thus demonstrated that visitors actively engaged with the stonework collection. Finally, one answer specifically pointed to the device encouraging deeper contemplation of the gods in the context of their own preferences and needs (P8; see below).

The second desideratum was that MRP changed behaviour inside the museum, aiding groups of visitors to overcome the passive, whisper environment of the Clayton Museum. Some visitors noted that they slowed down and observed the information around the stones, and made it interactive:

‘It should make children read information (hopefully) & me! I just couldn’t help myself!’ (P10)

‘Fun and engaging to myself an adult. It made me want to read more.’ (P54)

‘My eight-year-old son who usually doesn’t like museums liked this one, also got very interested in it thanks to the experience.’ (P12)

‘It made you read more about the remains and added to the experience.’ (P15)

‘It was more intuitive to use and made the visit more interactive.’ (P37)

‘I loved it, made it interesting and more interactive for visitors.’ (P11).

MRP also provoked discussion within groups.16 Observations noted conversations explicitly about the various choices that visitors made: one visitor was heard saying ‘I’ll have this Genius Loci — the spirit of the place’. In another case, a father and son were comparing their choices and the son said: ‘I’ve got wings, I’ve got money, and I’ve got war’ and the father said ‘Oooh you want Victory, she is the best’. In addition to the questionnaire, observations confirmed that MRP disrupted the reverence for the museum. If the lamp was not being used, the people tended to move slowly and spoke only occasionally and often in whispers, even shushing others into silence. Visitors with the votives exhibited dynamic movements between stopping points and were more vocal and louder during conversations. Conversations between parents and children were often explicitly about the activity. Children who at first visited the main room of the museum and did not engage with the collection, upon seeing someone else with a votive, sought one out and entered the museum a second time, exhibiting more engagement with their visit.

The final desideratum was that MRP restored the collection of archaeological stonework as loci of embodied experience — i.e. visitors feel they are actively placed in a world of gods, participating in a ‘ritual’ of significance. A range of respondents indicated that the experience was immersive and or experiential, one explicitly: ‘It was the best part of the visit it made the whole experience much more immersive & interactive’ (P12). A further three responses, while not explicitly mentioning immersivity, exhibited a deep reflection while completing MRP:

‘It was quite a unique idea … More thought provoking as it made you think more about the gods”, and ‘Juno god selection was quite thought provoking. Trying to work out which gods appealed to me, were benevolent; thought provoking’ (P8).

‘Made you think about what is important to you. Brilliant visit, have visited the other museums along the wall but found Chesters very informative’ (P36).

‘Nice to decide whether you really wanted to offer to this or that particular god. Choices reflected how I felt today’ (P41).

These visitors appear to exhibit a conscious sense of the importance of the experience and wanted to make choices that were personally meaningful to them. A host of responses explicitly indicated that they enjoyed the interactivity of the device, were engaged, and even felt excited:

‘It was exciting because I wanted to see my oracle and the walking part was cool too’ (P7).

‘Excited by lamps and lights; good to have interactive; could read the tap points’ (P9).

‘Love it! Brilliant way to make a dry (for kids) museum into something exciting’ (P55).17

The repeated explicit mention of excitement is indicative of what Jesse Prinz (2004) terms embodied emotion, a change of bodily state specifically provoked by certain emotions — e.g. excitement, fear, or dread. The use of the term ‘fun’ is another example of embodied emotion and occurs a further 10 times in the questionnaires.

Beyond hinting or stating MRP’s immersivity, some respondents explicitly revealed that it prompted them to focalise as if they were Romans: ‘It was fun. It felt like you went back to Roman Times — this is what they would have done — felt more personal — like you were a soldier here’ (P2). This is a curious comment in the context of an antiquarian museum that makes little attempt to engage with life through a Roman lens and a fort that is displayed with notable Victorianising elements, such as gated compounds around the remains. Perhaps most intriguingly, a subset of these respondents revealed MRP created interference with their own Christian belief system. One respondent made a seemingly opaque comment about the relativity of religious beliefs: ‘All civilisations develop their own systems of beliefs. So be opened minded (sic) and respect others’ (P39). Upon completion of the questionnaire, the respondent then reflected jovially on her response and said to the interviewer: ‘I had better not tell my pastor at my church that I made a votive offering to the Roman gods’. In the context of the oral answer, the written comment made more sense: it was perhaps a reflection upon her assumptions about the potential to see Roman ‘paganism’ negatively. The oral comment itself, although made light-heartedly, was seemingly an expression of worry that participation was an act that interfered with her own religious practice, if not in her own mind, but at least potentially in the minds of others. Two members of another family group more explicitly commented that participation in MRP had collided with their Christian beliefs. One boy noted: ‘It was fun but slightly weird to make offerings to gods who I believe don’t exist’ (P56). His mother also commented that ‘using the physical thing [the lamp] was great, but I felt very uncomfortable about it being presented as “making offerings to the gods” — it felt like this was asking my child to make a pagan offering in order to enjoy the museum (from a perspective of a Christian)’ (P57). It is evident that MRP was successful in affecting these visitors in a deep and emotional way, and prompting them to feel that the act of offering votives was in conflict and competition with their preferred religious practice, and participation risked them acting counter to their beliefs, pushing them to feel uncomfortable. This is even though the ‘ritual’ was a pastiche and, therefore, a testament to the success and, indeed the — potentially problematic — consequences of the mise-en-scene and embodied design. Finally, one visitor mentioned that ‘it is really fun and it makes me feel like I’m in a magic place because of the light coming in the little Juno votive devices. It’s really amazing’ (P13) — an expression of the effect of the technology, moving them from antiquarian Chesters to the supernatural realm of Roman gods. MRP was specifically responsible for enabling visitors to undertake an embodied and emotive experience of the Roman past.

Conclusion

The Clayton Museum showcases the history of antiquarianism and is a conservative interpretive environment. During the Victorian era, there was a movement away from the early ‘sensory’ museum towards a consensus on a public museum that imposed limits on behaviour — particularly direct tactile interaction with artefacts (Foster 2011; Thomas 2016). Sandra Dudley (2010: 3) observes in contemporary practice that

‘too often the possibilities of physical and emotional interaction with objects in museums are assumed to be non-existent or restricted to elitist, “pure, detached, aesthetic response”, unless they are enabled or underpinned by (largely textual) information provided by the museum’.

Derrick (2017: 77) has previously underlined the challenge of sensory approaches to museum display along Hadrian’s Wall, noting particularly mournfully in regard to Chesters that ‘if multi-sensory experiences at archaeological sites are ultimately desirable, then we still have a long way to go’. The installation of My Roman Pantheon changed the behaviour and the interpretive lens of the museum, showing what can be achieved in a seemingly unpromising context. The use of the senses, most notably touch, prompted re-engagement with Roman religion, rather than a collection of stonework. The evaluations show that the antiquarian order and associated behaviour were reconfigured to deliver engagement with the Roman past. Some visitors felt embodied in a world of gods, where they felt they made consequential choices.

Although conceived primarily as a means of interaction to fit in an audience profile and specific museological environment, MRP has important consequences for the deployment of interpretation aimed at enhancing sensory expression and experience in archaeological museums. It successfully targets specific segments of the museum visitorship, who might prefer a non-visual, non-information-centric experience, in an information-centric environment. While not specifically addressing visitors with ocular impairments, with some adaptations to the written output and instructions, the tactile interaction, and IoT technology could also be used to provide an equitable experience for impaired visitors. Finally, to return to the premise of this Special Issue. The proliferation of approaches to the senses in archaeology cannot just be accompanied by a ‘comeback’ for sensory museum spaces, it must be entwined with them. If we are to engage people with the returns on the practices of sensory archaeology, then museums must be capable of delivering it and equip a range of audiences to explore it. C.P. Foster (2011: 371) has bullishly claimed that ‘despite traditional practices, museums are suitable venues for presenting sensuous pasts’. While this paper has not dealt with the specific instance of translating the senses of the past, it is hoped that this study can show ways in which public museums can re-engage visitors sensorially, and prompt embodied experiences, while maintaining conservation requirements and balancing the needs of different audiences.

Additional Files

The additional files for this article can be found as follows:

Narrative of responses. DOI: https://doi.org/10.16995/traj.10600.s1

The Clayton Museum – Please Tell Us What You Think. DOI: https://doi.org/10.16995/traj.10600.s2

Notes

- These were one of three categories used during interpretation projects, based upon a series of annual data gathering exercises, and internal reports. [^]

- The choice was made to eschew 3D installations and large stand-alone graphic panels, audio-visual interpretation that might use sound or light, and to retain the historic cases where possible. [^]

- Albeit with some secondary, thematic reflections on Clayton and his colleagues and some on Roman military life particularly in the smaller of the two museum rooms. [^]

- Although Chesters hosts educational visits, the experience was geared towards self-guided family groups and not towards large practitioner-led school groups. MRP was not the entire offer for these groups. For example, an on-site role-playing family trail was instituted. [^]

- See n.1. [^]

- Visitors, furthermore, have a doubly dislocated experience, thanks to the museum building itself being separate from the fort by a few hundred metres, and often visited before the fort itself — i.e. the collection lacks its physical and conceptual context. While there are reconstructions of the buildings and people on the site graphic panels, once within the museum there were no figurative 2D graphics or 3D installations to place these objects in context. [^]

- Skeates and Day (2019: 12) note this attitude taken up by visitors to institutions such as the British Museum. Although Chesters is not on the same scale as its metropolitan precursors, it shares an aesthetic and inhabits a similar cultural space that cues visitors into similar behaviour and assumptions about the parameters of their visit. [^]

- This was noted anecdotally by both site staff and the project team — albeit this observation was consequently backed up by observations conducted during the evaluation of MRP (see evaluation discussion). [^]

- Juno also featured in the museum as one of the few pieces of figurative sculpture. [^]

- While this might be reasonably objected to on the grounds of mixing too many religious practices, the point of MRP was to demonstrate the power, influence, and importance of Roman gods, and not a specific ritual. [^]

- Note that these descriptions were not exhaustive of all aspects of the deity. [^]

- There have been some limited periods of inactivity due to technical issues and a long hiatus during, and immediately after, the COVID-19 pandemic. [^]

- The final two rounds of questionnaires were conducted in Spring 2023, and was completed with a shorter version focused on the sensory issues covered by this paper. [^]

- There are also a small number of additional marginalia capturing ad hoc thoughts during or after the questionnaire. All are quoted verbatim except for instances where additional thoughts were garnered verbally based upon a conversation, which took place after the completion of the questionnaire. In a small number of cases, the responder asked the interviewer instead to act as a scribe. [^]

- All P numbers refer to the responses listed in Appendix A. [^]

- For example, in P11: ‘I thought that using the Juno device made us talk more while walking around so we had more discussion about the Gods, goddesses and Nymphs.’ [^]

- See also P3, P4, and P6. [^]

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the creative input to the design of MRP by the design team: Frances McIntosh and Joe Savage for English Heritage, and Nick Dulake and Mark Marshall for Sheffield Hallam University, in addition to the Chesters’ site team for their help with running and evaluating MRP, and above all their enthusiasm for, and patience with, ‘Juno’. The research for My Roman Pantheon was partially supported by the project meSch (2013–2017) funded by the European Union’s FP7 (ICT Call 9: FP7-ICT-2011-9) under the Grant Agreement 600851. Finally, Dr Roberts would especially like to thank Ellie Mackin Roberts, who championed the approaches of this study, diligently commented on drafts, and without whom this would not have been completed.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

Adkins, Genevieve, Nigel Mills, and Hadrian’s Wall Heritage Ltd. 2011. Hadrian’s Wall Interpretation Framework: Overview and Summary: Frontiers of the Roman Empire World Heritage Site. Hexham: Hadrian’s Wall Heritage.

Burton, Gregory. 1993. Non-neural extensions of haptic sensitivity. Ecological Psychology 5: 105–124. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1207/s15326969eco0502_1

De Caro, Laura. 2015. Moulding the museum medium: explorations on embodied and multisensory experience in contemporary museum environments. ICOFOM Study Series 43b: 55–70. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4000/iss.397

Derrick, Thomas J. 2017. Sensory archaeologies: A Vindolanda smellscape. In: Eleanor Betts (ed.). Senses of the Empire. London: Routledge: 71–85. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4324/9781315608358-6

Dudley, Sandra H. 2010. Museum materialities – objects, sense and feeling. In: Sandra H. Dudley (ed.). Museum Materialities: Objects, Engagements, Interpretations. London: Taylor & Francis: 1–17.

Foster, Catherine P. 2011. Beyond the display case: creating a multisensory museum experience. In: Jo Day (ed.). Making Senses of the Past: Toward a Sensory Archaeology. Illustrated edition. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press: 371–389.

Garnett, Karen S. 1975. Late Roman Corinthian lamps from the Fountain of the Lamps. Hesperia 44(2): 173–206. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/147586

Gibson, James J. 1962. Observations on active touch. Psychological Review 69: 477–491. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1037/h0046962

Hingley, Richard. 2011. Rome: imperial and local religions. In: Timothy Insoll (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of Ritual and Religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press: 745–757. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199232444.013.0047

Hodgson, Nick. 2017. Hadrian’s Wall: Archaeology and History at the Limit of Rome’s Empire. Marlborough: Crowood Press.

Howes, David. 2022. Sensory museology: bringing the senses to museum visitors. In: David Howes (ed.). The Sensory Studies Manifesto: Tracking the Sensorial Revolution in the Arts and Human Sciences. Toronto: University of Toronto Press: 163–180. DOI: http://doi.org/10.3138/9781487528638-010

McIntosh, Frances C. 2019. The Clayton Collection: An Archaeological Appraisal of a 19th Century Collection of Roman Artefacts from Hadrian’s Wall. BAR British Series 646. Archaeology of Roman Britain Volume 1. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports. DOI: http://doi.org/10.30861/9781407321479

Pallasmaa, Juhani. 2014. Museum as an embodied experience. In: Nina Levent and Alvaro Pascual-Leone (eds). The Multisensory Museum: Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives on Touch, Sound, Smell, Memory, and Space. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield: 239–250.

Paterson, Mark. 2007. The Senses of Touch: Haptics, Affects and Technologies. London: Routledge.

Petrelli, Daniela. 2019. Tangible interaction meets material culture: reflections on the meSch project. Interactions 26(5): 34–39. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1145/3349268

Petrelli, Daniela and Sinead O’Brien. 2018. Phone vs. tangible in museums: A comparative study. In: Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. CHI ’18: CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Montreal: ACM: 1–12. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1145/3173574.3173686

Petrelli, Daniela and Roberts, Andrew J. 2023. Exploring digital means to engage visitors with Roman culture: Virtual Reality and Tangible Interaction. Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage 16(4): 1–18. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1145/3625367

Petrelli, Daniela, Nick Dulake, Mark T. Marshall, Andrew Roberts, Frances McIntosh, Joe Savage. 2018. Exploring the potential of the Internet of Things at a heritage site through Co-design practice. In: 2018 3rd Digital Heritage International Congress (DigitalHERITAGE) held jointly with 2018 24th International Conference on Virtual Systems & Multimedia (VSMM 2018). San Francisco, CA: IEEE: 1–8. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1109/DigitalHeritage.2018.8810061

Prinz, Jesse. 2004. Embodied emotions. In: Robert C. Solomon (ed.). Thinking About Feeling: Contemporary Philosophers on Emotions. Oxford: Oxford University Press: 44–58. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780195153170.003.0004

Roberts, Andrew J. 2021. An exhibition of their own: designing a family-friendly experience at Birdoswald Roman fort. In: Nigel Mills (ed.). Visitor Experiences and Audiences for the Roman Frontiers. BAR International Series 3066. Oxford: BAR Publishing: 41–54. DOI: http://doi.org/10.30861/9781407359007

Skeates, Robin and Jo Day. 2019. Sensory archaeology. Key concepts and debates. In: Robin Skeates and Jo Day (eds). The Routledge Handbook of Sensory Archaeology. London: Routledge: 1–17. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4324/9781315560175-1

Sonneveld, Marieke H. and Hendrik N.J. Schifferstein. 2008. The tactual experience of objects. In: Hendrik N.J. Schifferstein and Paul Hekkert (eds). Product Experience. Amsterdam: Elsevier Sciences: 41–67. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/B978-008045089-6.50005-8

Thomas, Nicholas. 2016. The Return of Curiosity: What Museums are Good for in the 21st Century. London: Reaktion Books.

von Lehn, Dirk and Christian Heath. 2003. Displacing the object: mobile technology and interpretive resources. In: Cultural institutions and digital technology, ICHIM Paris, 08–12 September 2003: 1–15.